Evaporites is the collective name for a wide-ranging group of sedimentary mineral deposits. They form by evaporation from aqueous solution, primarily in brine-rich marine environments but also in certain freshwater settings where the water has a high mineral content.

They are typically associated with hot arid or semi-arid climates, where the loss of water through evaporation is greater than the rate of precipitation. The minerals that crystallise as the water volume reduces are dependent upon the residual chemistry, typically forming chloride, sulphate and carbonate compounds.

Common examples of evaporite minerals include gypsum (calcium sulphate dihydrate), anhydrite (calcium sulphate), halite (rock salt – sodium chloride), and potash (potassium carbonate & related compounds).

The unique environment in which evaporites form means they are relatively rare in the UK’s geological record. However, their chemistry means they are commercially important as raw materials in a range of agricultural, industrial and retail industries. Examples of the use of common evaporates include:

- Gypsum: Is a main component of; plaster and plasterboard used in the construction sector; agricultural fertiliser, pharmaceuticals, and as an additive in the food and drinks industry (e.g. adding hardness to water used in brewing).

- Halite: Salt, salt and more salt! Most obviously in the preservation and curing of food, and as one half of the famous condiment duo! It is also widely used as de-icer on roads. The raw material is used the chemical industry in the preparation of a range of other chemicals including sodium hydroxide, soda ash, hydrochloric acid, chlorine and metallic sodium.

- Potash: Most widely used within the agricultural industry as a nutrient and a constituent of fertiliser. Also used in water conditioners, detergents, and in the ceramics industry.

- Alum: Used for fixing dye in textiles, Alum became an important industry in the from the 16th century as prior to that it was imported from Spain and Italy where its export was tightly controlled by the Vatican. However, when Henry VIII fell out with the Pope, the search for a domestic source ensued. Alum was mined commercially until the later 19th century when alternative production methods were used.

Evaporite Geology in the UK

There were three periods of evaporite deposition in the UK, namely

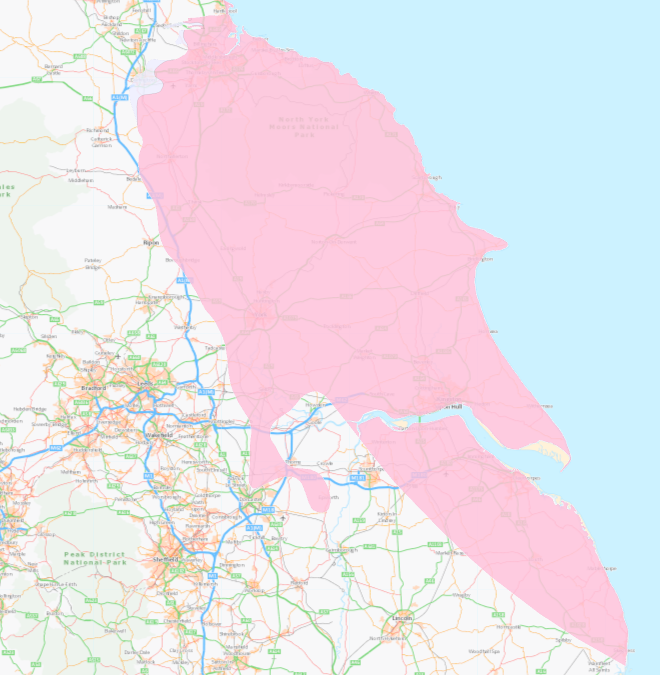

- Late Permian successions (270-250 ma): occurring in subsurface formations of the Zechstein Group in north-east England and much smaller volumes in Cumbria. The Permian geology is a rich source of gypsum, halite and potash.

- Mid-Late Triassic successions (240-201 ma): Halite beds within the Mercia Mudstone Group are found extensively in Cheshire and to a lesser extent in Staffordshire (Stafford) and Worcestershire (Droitwich). Significant gypsum beds of Triassic age are found primarily in the East Midlands (Nottinghamshire, Leicestershire and Staffordshire) as well as in Somerset.

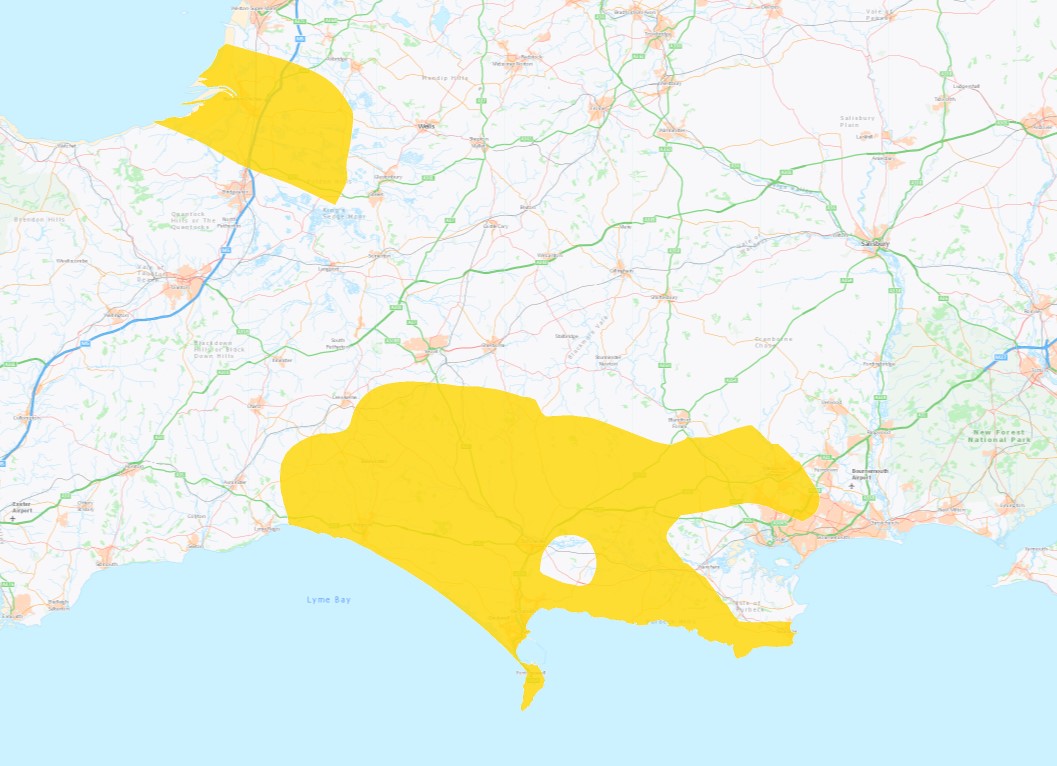

- Late Jurassic successions (140-150 ma): The Whitby Mudstone of the Cleveland Basin was an important source of both ironstone (which we have covered in a previous post) and alum. Evaporites can also be found in the Weald Basin (Kent), although these were generally not economically recoverable and the Wessex Basin (Dorset) where deposits have been mined, but to a much lesser extent than other areas of the UK.

Subsurface extent of Permian evaporite deposits in NE England. All data courtesy of the British Geological Survey. British Geological Survey materials © UKRI 2024

Mining History and Techniques

The evaporite minerals have differing mining histories reflecting their use and adoption within human history. Halite (rock salt) has been extracted and used as a food preserver since Roman Times. There is evidence for gypsum mining from the 12th century (e.g. alabaster carvings in Staffordshire), although extraction only really increased during the industrial revolution. On the other hand, Potash mining in England is very much a post-war industry.

Evaporites are soluble in water and therefore rarely found at surface levels (because rainwater readily dissolves them into solution). All deposits in the UK are therefore found underground which means subsurface mining is the only option.

Most of the evaporite minerals are extracted by traditional underground methods such as pillar and stall, adit mining, and longwall mining. Halite and occasionally potash is also extracted by solution mining, where water is pumped into subterranean deposits to dissolve the salts with the resulting brine being pumped back to the surface for drying and salt extraction.

Remnant Hazards and the Risks to Landowners and Developers

All the main evaporite areas of the UK have been extensively mined at some stage over the past three hundred years. Many of these workings, especially during the industrial revolution, were unregulated and undocumented. The result is a landscape littered with both recorded and unrecorded mine workings and many of the locations have now been long forgotten which create hazards for landowners and developers.

These historic mine workings are highly susceptible to land subsidence and even collapse. Another problem is that evaporite minerals are highly soluble, meaning water ingress can dissolve remnant deposits not extracted at the time of mining. Some mines that were safe and stable at the time of operation may subsequently become unstable as these remnant deposits are dissolved as water enters the mine. This is only expected to increase with climate change producing more frequent and intense rainfall events and rising groundwater levels.

The most significant risk is in areas where salt was mined using brine extraction and examples can be seen around Nantwich where mine collapses have manifested flashes (where depressions caused by ground subsidence become filled with water) the largest of which is over 35 hectares in area. Gypsum mining also poses a significant risk in the Midlands (that’s not to say other areas are not at risk) and salt and alum extraction also pose a risk in the Cleveland and North Yorkshire regions respectively. Potash extraction did not begin until post WWII and is at significant depth (over 1000m) and as such does not pose a significant risk.

GRM have extensive experience and expertise working with landowners and developers to help identify historic mine workings and mitigate risk. If you have any development or construction projects that may be impacted by historical mining workings and hazards, then please get in touch to find out how we can help save both time and costs. Please use your main point of contact at GRM or for new enquiries email richard.upton@grm-uk.com or call 01283 551249.