Chalk is one of the UK’s most recognisable rocks thanks largely to its vibrant white colour and the vast iconic cliffs that occur along the south coast. It is found across large parts of the south and southeast of England and forms an extensive band which runs northwards across East Anglia and into the northeast of England (see map below produced and courtesy of the British Geological Survey).

All the chalk in the UK and Europe formed during the late Cretaceous period approximately 100-60 million years ago (Creta is Latin for chalk). It is made up of almost pure calcite (CaCO3), which formed from microscopic plankton and fragments of larger marine creatures that sank to the bottom of deep oceans and became compacted over time.

British Geological Survey materials © UKRI 2024

Chalk is primarily used in the construction industry as a constituent of quicklime, cement, and to make bricks. Its alkaline properties also mean it can be used in agriculture to raise the pH of acidic soils. And we should not forget its use as blackboard chalk in the classroom – at least for us older generations!

The mining of chalk has occurred for centuries, reaching its peak during the industrial revolution when there was extensive construction and demand for building materials. Mining and extraction of chalk continues today with active mines across all the key chalk areas including Kent, Sussex, Berkshire, Hampshire, East Anglia and Humberside.

Flint Mining

It is also worth noting the close association between chalk and flint, which are often interbedded within Cretaceous deposits. Flint is primarily made up of quartz (silica), which form as nodules and larger bands of rock. The hardness of flint and fracturing qualities means it readily breaks and chips into sharp edge pieces, which have been used as tools for thousands of years most notably during the Stone Age. It has also been used as a building material for houses, roadworks and boundary walls.

Chalk Mining Techniques

Chalk has historically been extracted through surface quarries and underground mines. The relative softness of the rock means it could be excavated using manual labour employing simple pick and shovel techniques with the spoil being removed in wheelbarrows and more recently by mechanical means.

The mines themselves were often extensive both in terms of their length and the height of the chambers. The working face consisted of a series of stepped benches which allowed several groups of miners to work the same face at the same time. Chalk mines are often located directly below brickfields.

Emmer Green chalk mine in Reading is an excellent example of one of these large underground workings, which is accessed by a 50ft (15m) deep shaft (see pictures below). It is thought to date back to the early construction of the town in the 1600s and was rediscovered in 1977 during building works. The various chalk deposits at Emmer Green are interbedded with flint layers and nodules.

Remnant Hazards and the Risks to Landowners and Developers

All the main chalk areas of the UK have been extensively mined at some stage over the past three hundred years. Many of these workings, especially during the industrial revolution, were unregulated and undocumented. The result is a landscape littered with both recorded and unrecorded mine workings and many of the locations have now been long forgotten which create hazards for landowners and developers.

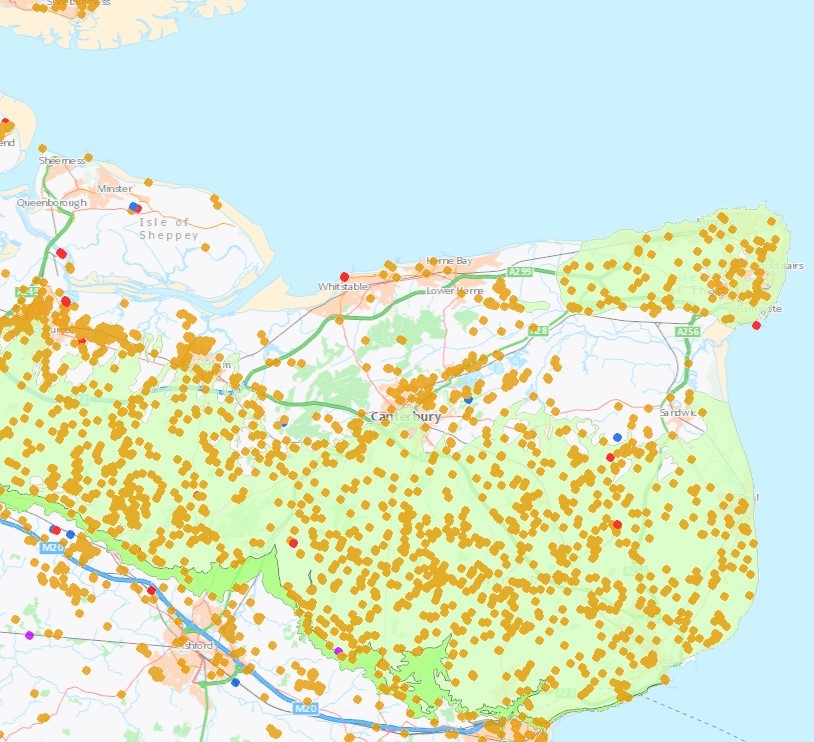

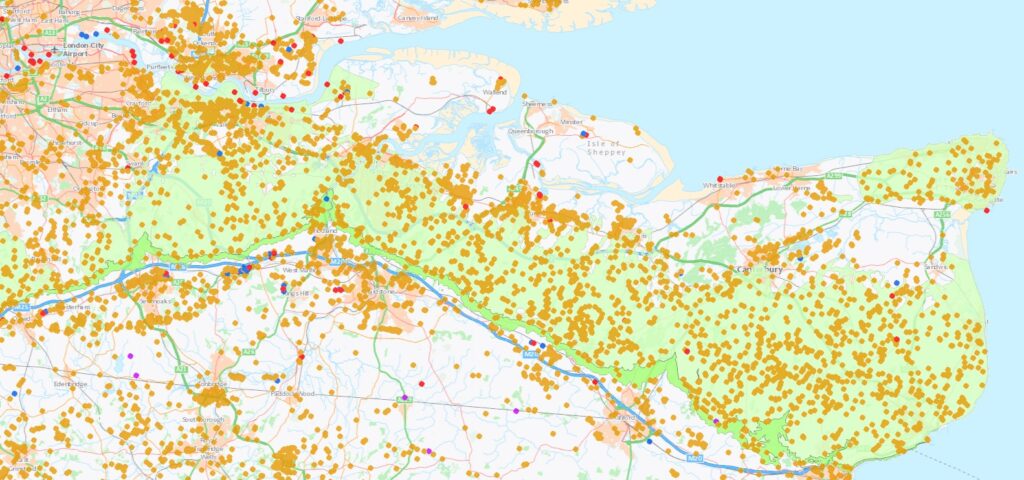

Chalk deposits across SE London and Kent (green) and known historic and active mining areas (historic – brown dots, active – red dots). Compiled from British Geological Survey materials © UKRI 2024.

One of the main problems is that chalk is highly soluble, meaning rainfall can dissolve rocks that overlay and surround historic mine shafts and workings. This leads to ground subsidence and in some cases even collapse. This is only expected to increase with climate change producing more frequent and intense rainfall events.

Examples of collapsed chalk mine workings and sinkholes appearing are frequently reported in the media. These include high profile examples in Reading (close to the Emmer Green mine), St Albans, Plumstead in South London, and Pinner in North London. And not forgetting the iconic ‘bus in a sinkhole’ story and photo from Norwich in 1988: The sinkhole that swallowed a bus in Norwich – BBC News

GRM have extensive experience and expertise working with landowners and developers to help identify historic mine workings and mitigate risk. If you have any development or construction projects that may be impacted by historical mining workings and hazards, then please get in touch to find out how we can help save both time and costs. Please use your main point of contact at GRM or for new enquiries email richard.upton@grm-uk.com or call 01283 551249.